FITA Magazine Vol. I / Invisible Atlas

Alberto Manguel

Interview by Francisco Teles da Gama

![]()

Photograph © Bruno Simão

The author we have before us is a passionate reader, who built imaginary kingdoms and labyrinths, surrounded by towers of books, carried on the wings of the hippogriff, embarked on Long John Silver’s ship, alongside Alice in Wonderland. His life was marked by countless travels, eventually adopting literature as his only nationality. In these sudden changes of country, books gave him the cozy feeling of home. That home was immortalized in the library he founded in the Loire valley, which is now in Lisbon, with an extension of more than 40.000 books. The works The Library at Night and Packing My Library recount the importance of this place he created to immortalize his passion for reading, making the library an independent space without borders. The Dictionary of Imaginary Places describes in detail all the places invented by writers during centuries of human existence. Obviously Manguel does not forget the surrealistic cities described by Marco Polo in Italo Calvino’s immortal work. For these reasons, it is not surprising that he became director of the Biblioteca Nacional of Argentina.

Once one of the greatest writers of the 20th century, who was also director of the same Biblioteca Nacional, invited Alberto Manguel to be his personal secretary. Manguel was 16 years old, working at the Pygmalion bookstore, and the writer who met him that day was Jorge Luis Borges. Borges left us countless works in genres as diverse as poetry, short fiction, mythology with The Book of the Imaginary Beings, and travel literature through the book Atlas, where he leaves us a fascinating testimony about the destinations that captivated him. Venice assumes a prominent role there, as in Manguel’s life and work.

Alberto Manguel takes on the role of literature scholar, always reminding us of the unsurpassable power of reading to change the world. He has published numerous books that tell us the story of the human genius, examples of the survival of curiosity, which visits us at all hours. After living in Israel, France, Canada, Argentina and Portugal, he now declares that it is a dream to live in the same city that was once inhabited by Fernando Pessoa. Legends tell that Lisbon was founded by Ulysses, another literary epitet so real for all of us. It is in this capital that Alberto Manguel directs the Centro de Estudos de História da Leitura, where he opens the doors to his infinite library.

Since you were a child you have built temples and castles with the piles of books you read, creating a universe all of your own. Do you still marvel at the novels and short stories you discover today?

Reading is an ongoing adventure constantly leading to the discovery of new texts, because literature is an ongoing, constant creation. Behind the horizon of every page lies another page, and we will never explore the entire cosmic volume.

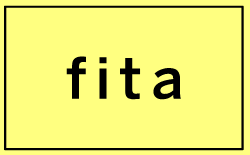

![]()

Photograph © Tinta-da-China

When you created your library in the Loire Valley, with more than 40.000 copies, did you expect to find your own country? And now that these literary masterpieces are at everyone’s service in the Centro de Estudos de História da Leitura, in the Marqueses de Pombal Palace in Lisbon, do you feel you have opened the doors of this kingdom to all literature lovers?

Marguerite Yourcenar used to say: “My homeland are my books.” Yes, my library in the Loire valley was my homeland. I’ve never believed in the nationality bureaucratically decreed by a passport. A shared library is a country that welcomes all, and I hope that the Centro de Estudos de História da Leitura will be exactly that.

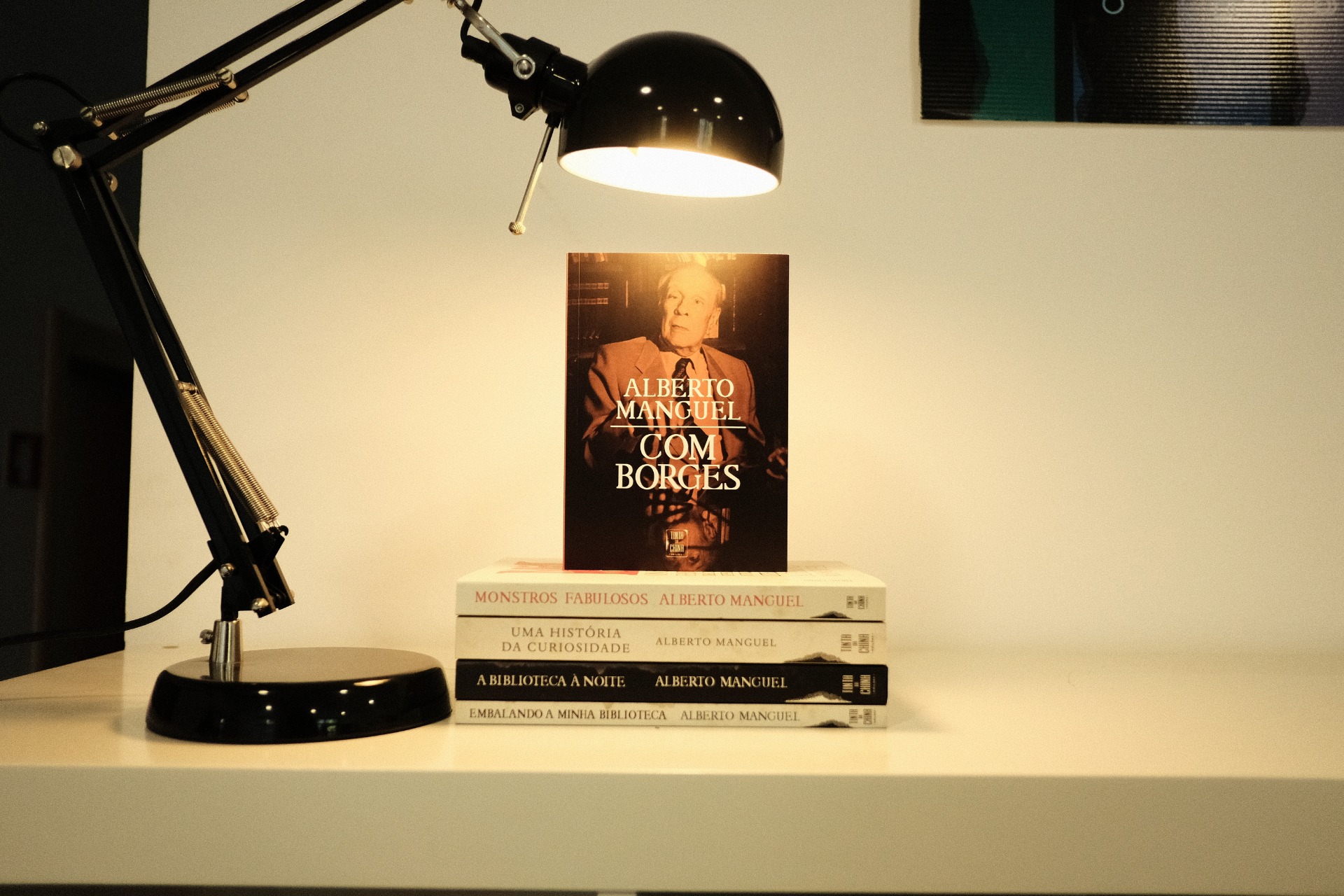

In your work The Library at Night you praise the silence of the night for having all the peace you need to enjoy a good book. Does the night help you to write and to let your imagination flourish?

I read well at night; I write in the morning. I wake up very early, make myself a tea from Companhia Portugueza de Chá, and then begin my day making a few notes on the canto of Dante’s Commedia I’ve read that day. Then have breakfast and after breakfast I start to write. I stop at midday. In the afternoon and in the evening I read or do obligatory tasks like answering the questions of yet another interview.

![]()

Photograph © Tinta-da-China

Alberto Manguel

The Bookshelves Of

Alexandria’s New Library

Interview by Francisco Teles da Gama

Photograph © Bruno Simão

The author we have before us is a passionate reader, who built imaginary kingdoms and labyrinths, surrounded by towers of books, carried on the wings of the hippogriff, embarked on Long John Silver’s ship, alongside Alice in Wonderland. His life was marked by countless travels, eventually adopting literature as his only nationality. In these sudden changes of country, books gave him the cozy feeling of home. That home was immortalized in the library he founded in the Loire valley, which is now in Lisbon, with an extension of more than 40.000 books. The works The Library at Night and Packing My Library recount the importance of this place he created to immortalize his passion for reading, making the library an independent space without borders. The Dictionary of Imaginary Places describes in detail all the places invented by writers during centuries of human existence. Obviously Manguel does not forget the surrealistic cities described by Marco Polo in Italo Calvino’s immortal work. For these reasons, it is not surprising that he became director of the Biblioteca Nacional of Argentina.

Once one of the greatest writers of the 20th century, who was also director of the same Biblioteca Nacional, invited Alberto Manguel to be his personal secretary. Manguel was 16 years old, working at the Pygmalion bookstore, and the writer who met him that day was Jorge Luis Borges. Borges left us countless works in genres as diverse as poetry, short fiction, mythology with The Book of the Imaginary Beings, and travel literature through the book Atlas, where he leaves us a fascinating testimony about the destinations that captivated him. Venice assumes a prominent role there, as in Manguel’s life and work.

Alberto Manguel takes on the role of literature scholar, always reminding us of the unsurpassable power of reading to change the world. He has published numerous books that tell us the story of the human genius, examples of the survival of curiosity, which visits us at all hours. After living in Israel, France, Canada, Argentina and Portugal, he now declares that it is a dream to live in the same city that was once inhabited by Fernando Pessoa. Legends tell that Lisbon was founded by Ulysses, another literary epitet so real for all of us. It is in this capital that Alberto Manguel directs the Centro de Estudos de História da Leitura, where he opens the doors to his infinite library.

Since you were a child you have built temples and castles with the piles of books you read, creating a universe all of your own. Do you still marvel at the novels and short stories you discover today?

Reading is an ongoing adventure constantly leading to the discovery of new texts, because literature is an ongoing, constant creation. Behind the horizon of every page lies another page, and we will never explore the entire cosmic volume.

Photograph © Tinta-da-China

When you created your library in the Loire Valley, with more than 40.000 copies, did you expect to find your own country? And now that these literary masterpieces are at everyone’s service in the Centro de Estudos de História da Leitura, in the Marqueses de Pombal Palace in Lisbon, do you feel you have opened the doors of this kingdom to all literature lovers?

Marguerite Yourcenar used to say: “My homeland are my books.” Yes, my library in the Loire valley was my homeland. I’ve never believed in the nationality bureaucratically decreed by a passport. A shared library is a country that welcomes all, and I hope that the Centro de Estudos de História da Leitura will be exactly that.

In your work The Library at Night you praise the silence of the night for having all the peace you need to enjoy a good book. Does the night help you to write and to let your imagination flourish?

I read well at night; I write in the morning. I wake up very early, make myself a tea from Companhia Portugueza de Chá, and then begin my day making a few notes on the canto of Dante’s Commedia I’ve read that day. Then have breakfast and after breakfast I start to write. I stop at midday. In the afternoon and in the evening I read or do obligatory tasks like answering the questions of yet another interview.

Photograph © Tinta-da-China

Jorge Luis Borges revolutionized short story

writing and brought this literary genre to

the forefront. How do you see this form of

storytelling and Borges’ testimony to changing its paradigm?

The short story (like all other literary forms) is constantly changing. The writer establishes with the reader a new contract at every turning page. The conventions that the reader comes to accept in a short story will vary, say, from the fables of Aesop to those of today. So the reader always works with a certain sense of unexpectedness: how will the writer trick me now? Borges used the conventions of the essay to write his fictions, and make the reader believe that what is invented is real, but strategies like this were employed much earlier. Denis Diderot in 1772 wrote a story called “This Is Not a Short Story” in which he did just that. In that case, what should the reader do? Believe Diderot or believe the text? In the case of Borges, should the reader read “Pierre Menard” as an essay or as a fiction? Both ways, of course. And these multiple levels of reading constantly enrich the text.

The Dictionary of Imaginary Places is a hymn to all those idyllic worlds where readers dwell. It is fascinating to find latitudes so far away in space and also in time where they were created, by the laborious writers and cartographers. Which of all these imaginary destinations would you like to live in?

It also chronicles terrible places where you would not want to live, or even visit. In fact, I don’t think I would want to live in any imaginary place: I love our real suffering world too much.

Italo Calvino created several metropolises in his famous book The Invisible Cities, which you describe so well in your book The Dictionary of Imaginary Places. What weight did this book have on your way of seeing, writing and reading?

Calvino had the brilliant idea of describing Venice, which is impossible to describe, by turning the city into a kaleidoscope and reflecting the real Venice in dozens of imaginary ones, all partly Venice. Calvino’s book was a surprise to me, but I don’t think it influenced my way of reading or writing. Calvino’s voice is unique.

![]()

Photograph © Tinta-da-China

There are several literary characters who are so real in our lives that we think we have always known them, like Robinson Crusoe. In other cases, we meet historical figures who do not live between reality and fiction, like Gilgamesh. In the book Fabulous Monsters: Dracula, Alice, Superman and Other Literary Friends we meet some of these mythical beings, similar to The Book of the Imaginary Beings by Jorge Luis Borges. Are these literary friends usually present in your life?

They are always present: Alice is with me all the time, as are The Man Who Was Thursday and Dante the Pilgrim. Right now I am living with the fabulous monsters of Sandro William Junqueira’s Um piano para cavalos altos.

Jorge Luis Borges’ Atlas reveals a fascination for Venice, as you do in Curiosity. I know you spent most of your life as a traveler, before you chose to live in Lisbon. From these crossings, where literature was your nation, do you think Venice is the most suitable destination for artists?

It depends on the artist. I think Lobo Antunes would be miserable in Venice; I don’t think Margaret Atwood would find it a city comfortable to live in. I myself love Venice because I think it’s the most beautiful city in the world, together with the Alhambra. But I find Lisbon (for the time being) perfect for my restless soul.

![]()

![]()

Photographs © Tinta-da-China

Through the works Curiosity and A History of Reading we understand the importance of the past in your narrative and vision of the universe. In your opinion, is History the key to the future?

Past, present and future are inventions of the human brain. In the universe of astrophysics, there is nothing but space-time, a continuum of time and space in which everything is and occurs simultaneously. So, to see in the past, clues for the future may be to recognize, perhaps unconsciously, that we were and will be from birth to death in the same moment we are now. Like understanding that the roots of a tree are part of its branches, or understanding that the child we once were lives inside the old man we see in the mirror today.

The interview to Alberto Manguel was published on pages 22 to 26 in Winds of Change chapter of FITA Magazine Vol. I / Invisible Atlas dedicated to the city of Venice.

The short story (like all other literary forms) is constantly changing. The writer establishes with the reader a new contract at every turning page. The conventions that the reader comes to accept in a short story will vary, say, from the fables of Aesop to those of today. So the reader always works with a certain sense of unexpectedness: how will the writer trick me now? Borges used the conventions of the essay to write his fictions, and make the reader believe that what is invented is real, but strategies like this were employed much earlier. Denis Diderot in 1772 wrote a story called “This Is Not a Short Story” in which he did just that. In that case, what should the reader do? Believe Diderot or believe the text? In the case of Borges, should the reader read “Pierre Menard” as an essay or as a fiction? Both ways, of course. And these multiple levels of reading constantly enrich the text.

The Dictionary of Imaginary Places is a hymn to all those idyllic worlds where readers dwell. It is fascinating to find latitudes so far away in space and also in time where they were created, by the laborious writers and cartographers. Which of all these imaginary destinations would you like to live in?

It also chronicles terrible places where you would not want to live, or even visit. In fact, I don’t think I would want to live in any imaginary place: I love our real suffering world too much.

Italo Calvino created several metropolises in his famous book The Invisible Cities, which you describe so well in your book The Dictionary of Imaginary Places. What weight did this book have on your way of seeing, writing and reading?

Calvino had the brilliant idea of describing Venice, which is impossible to describe, by turning the city into a kaleidoscope and reflecting the real Venice in dozens of imaginary ones, all partly Venice. Calvino’s book was a surprise to me, but I don’t think it influenced my way of reading or writing. Calvino’s voice is unique.

Photograph © Tinta-da-China

There are several literary characters who are so real in our lives that we think we have always known them, like Robinson Crusoe. In other cases, we meet historical figures who do not live between reality and fiction, like Gilgamesh. In the book Fabulous Monsters: Dracula, Alice, Superman and Other Literary Friends we meet some of these mythical beings, similar to The Book of the Imaginary Beings by Jorge Luis Borges. Are these literary friends usually present in your life?

They are always present: Alice is with me all the time, as are The Man Who Was Thursday and Dante the Pilgrim. Right now I am living with the fabulous monsters of Sandro William Junqueira’s Um piano para cavalos altos.

Jorge Luis Borges’ Atlas reveals a fascination for Venice, as you do in Curiosity. I know you spent most of your life as a traveler, before you chose to live in Lisbon. From these crossings, where literature was your nation, do you think Venice is the most suitable destination for artists?

It depends on the artist. I think Lobo Antunes would be miserable in Venice; I don’t think Margaret Atwood would find it a city comfortable to live in. I myself love Venice because I think it’s the most beautiful city in the world, together with the Alhambra. But I find Lisbon (for the time being) perfect for my restless soul.

Photographs © Tinta-da-China

Through the works Curiosity and A History of Reading we understand the importance of the past in your narrative and vision of the universe. In your opinion, is History the key to the future?

Past, present and future are inventions of the human brain. In the universe of astrophysics, there is nothing but space-time, a continuum of time and space in which everything is and occurs simultaneously. So, to see in the past, clues for the future may be to recognize, perhaps unconsciously, that we were and will be from birth to death in the same moment we are now. Like understanding that the roots of a tree are part of its branches, or understanding that the child we once were lives inside the old man we see in the mirror today.

The interview to Alberto Manguel was published on pages 22 to 26 in Winds of Change chapter of FITA Magazine Vol. I / Invisible Atlas dedicated to the city of Venice.